The Best and Worst FinCrime Takes of 2023

Moral clarity, new orthodoxies, and corruption that just won't quit...

*The views expressed in this post are my own and do not represent the views of my employer*

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind? I should hope not.

Lest we fail to reflect on all we’ve experienced over the past year. And nowhere is this more-true than in the realms of AML regulation, financial crime investigation, and policymaking related to illicit finance. 2023 was distinct from 2022, with shifts towards stability for the future of regulatory frameworks and some profound statements of moral clarity. We saw the trend of a return to normalcy continue, with prosecutors and policymakers seeking to push the agenda rather than letting the forces of COVID’s externalities set priorities. And yet we still find ourselves confounded by current events. How do we manage the interplay between law enforcement and diplomacy to address global money laundering? Is the AML world ready for artificial intelligence? Can we truly hold any of our political figures accountable in this day and age?

Putting together this list is always a journey down memory lane, revisiting the themes I wanted to explore in much longer pieces but didn’t quite flesh out. But instead of just an assemblage of takes that were good and bad, I like to think this year’s list demonstrates a more cohesive perspective on what the implications of this year’s events really were and how they may impact the future. But of course—you be the judge. For auld lang syne, I present the best and worst financial crime takes of 2023:

BEST - The Thursday Afternoon Conviction of Sam Bankman Fried

The coverage of the month-long trial of Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced founder of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, was anything but understated. Major news organizations, social media personalities, bloggers, and of course podcasters, all descended upon the trial, creating mountains of content that deconstructed every element of the process. The charges, the arguments, the witnesses, jury deliberations, sentencing considerations—it was all under a microscope that dissected even the smallest details, mining them for content. Judging Sam, Spellcaster: The Fall of Sam Bankman Fried, The Trial of Crypto’s Golden Boy, The Naked Emperor—you’d think they’d run out of titles eventually.

But alas, this fixation makes sense. First of all, this is the first major cryptocurrency fraud trial focused specifically on the actions and culpability of a founder. While there have been major fraud trials in the past (Enron and Theranos come to mind), this is the first trial featuring the founder a significant crypto platform being accused of defrauding customers.

Secondly, SBF’s history of political contributions and dedication to effective altruism provided a unique backdrop of intrigue. Would trying to do good absolve SBF of responsibility for his actions in the eyes of the jury? Would the nature of crypto as a technology and the complicated internal workings of the company introduce sufficient reasonable doubt that could impact the verdict?

But what I think ratcheted attention to a fever pitch was that this trial was the latest and greatest of a certain genre of fraud story. Since 2016, there’s been a healthy appetite for a specific kind of criminal narrative. Mainly—the eccentric sociopath who fooled everyone into believing they were the real deal. Individuals that rose to the highest echelons of society—who had rubbed elbows with the elite, who had been on the cover of Forbes, who had taken shots of rum with Ja Rule—but ended up being nothing more than a folktale. A few missteps pulling back the curtain to reveal their true nature.

We all know their names. Billy McFarland, Anna Delvey, Elizabeth Holmes. We’re almost obsessed with them, holding a certain quiet admiration for their unique ability to fool so many people for so long. And SBF is a heightened version of all those that had come before. What if you combined the elite bonfides of Holmes, with the hypebeast-adjacent swagger of McFarland, with the sheer weirdness of Delvey? Throw in some strange supporting characters and I’ll tell you, you’d have a really great 10-episode podcast. That’s the face of a series that launches thousands of MeUndies subscriptions.

But apparently no one told the SBF jury that their objective was to keep audiences clamoring. As commentator after commentator told the public that we’d likely have to wait days and maybe weeks to reach a verdict in the case. The jury quickly and diligently rendered guilty verdicts on all the charges levied against Bankman-Fried.

Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud on Customers: Guilty.

Wire Fraud on Customers: Guilty.

Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud on Lenders: Guilty.

Wire Fraud on Lenders: Guilty.

Conspiracy to Commit Commodities Fraud: Guilty.

Conspiracy to Commit Securities Fraud: Guilty.

Conspiracy to Commit Money Laundering: Guilty.

In just four and a half hours—over the course of an afternoon—the jury was able to review the evidence, assess witness testimony, and agree that Bankman-Fried had committed wide-reaching fraud against FTX’s customers and lenders. This was a victory thanks in no small part to the prosecutors who presented the case and the cooperation they received from Bankman-Fried’s one-time collaborators, but also the common-sense of ordinary people.

Even in the face of a media circus, the SBF jury focused singularly on the evidence put before them, seeing past the personalities and the mysticism many wanted to assign to both cryptocurrency and SBF himself, and instead seeing him for what he was, a criminal.

As I’ve said before, it’s understandable that we get caught up in the intrigue surrounding cases like FTX, which feature novel financial instruments and eccentric bedfellows. But we shouldn’t let our excitement about a good story cloud our moral judgement. We all love a good narrative, but that shouldn’t come at the expense of a just conclusion, even if it forces us to end our docuseries a few episodes early.

WORST – The New York Times’ Curious Commentary on Account Closures

Over the course of the past year, the New York Times has written multiple articles examining the phenomenon of abrupt bank account closures—the sudden and often unexplained closing of customer accounts that occurs without notice and causes significant disruptions in peoples’ lives. In the Times coverage, a series of vignettes of customer experiences is shared, demonstrating how behavior that they viewed as innocuous or actions they had no idea raised red flags, led to these sudden account shutdowns. These stories paint a picture of institutions taking unfair actions against their customers, quite literally leaving them at a loss (unable to access their funds), and also leaving them in the dark with regards to why.

The focus on this issue is understandable, as the sudden closure of accounts has the potential to significantly disrupt business operations and jeopardize important transactions such as rent or mortgage payments. As the Times explains, these closures are disconcerting in both their sudden nature and because it can take customers weeks to regain possession of their funds. It’s a major consumer protection concern.

So why is this designated as one of my worst financial crime takes of 2023? Because this coverage fails to accurately identify the complex reasons behind institutional account closure decisions, instead choosing to place blame squarely on the process of suspicious activity reporting.

Let’s start with the New York Times’ premise. The earliest of their articles was published in April and highlighted that account closures were on the rise due to growing fraud concerns related to the pandemic. They rightly assess that these closures were occurring without clear grounds, and that there was little recourse customers could seek in these situations. The Times also rightly identified that this is an issue worthy of scrutiny—are we protecting the financial system or simply impeding access out of an abundance of caution?

But the problem starts when the Times identifies the filing of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) as the culprit for these closures. According to their coverage, the closure of accounts is intrinsically tied to SAR filings, meaning that the majority of account closures that occur are because of suspected criminal activity. They argue, “These situations are what banks refer to as ‘exiting’ or ‘de-risking.’ This isn’t your standard boot for people who have bounced too many checks. Instead, a vast security apparatus has kicked into gear, starting with regulators in Washington and trickling down to bank security managers and branch staff eyeballing customers. The goal is to crack down on fraud, terrorism, money laundering, human trafficking and other crimes.”

This argument is expanded upon in later pieces, as the experiences of real customers are presented as proof-positive that SAR reporting is over-zealous, with potential negative implications for customer reputation. They state, “As if the lack of explanation and recourse were not enough, once customers have moved on, they don’t know whether there is a black mark somewhere on their permanent records that will cause a repeat episode at another bank. If the bank has filed a SAR, it isn’t legally allowed to tell you, and the federal government prosecutes only a small fraction of the people whom the banks document in their SARs.” The implicit argument is that there is something untoward about SAR reporting, that this isn’t the way the system is designed, and that there should be some recourse for customers in regards to the risk-based decisions made by financial institutions.

The problem here is that even though the Times “examined” over 500 cases of account closure and spoke to more than a dozen current and former industry insiders about this phenomenon, they failed to uncover the nuanced truth that while SAR filings and account closures can be linked, explicit concerns about money laundering are not what drives many account closures. In fact, the Times actually defines the terms surrounding this issue incorrectly, failing to recognize the role that an institution’s broader risk tolerance and their terms of service have on which accounts are closed.

Where I think the Times goes wrong is in the misleading definitions it provides to key terms early in its coverage. The first of these is de-risking. In the November 5th piece, writers Ron Lieber and Tara Siegel Bernard define de-risking as any situation in which a financial institution chooses to exit the customer relationship. While this is narrowly true, it’s important not to synonymize de-risking with risk-based exit decisions that come as a component of an investigative process. In the context of institutional financial crime programs, risk-based exit decisions are made based on unusual behavior by the customer which is then subject to a robust investigative process. These processes often result in a SAR filing, but not always. On the other hand, de-risking is a much broader action by an institution that isn’t based on individual customer conduct but rather customer characteristics that an institution identifies as outside of its preferred risk tolerance. Based on these characteristics, which can pose broad financial crime risks to the institution, they may choose to exit certain customer relationships.

For example, let’s say there’s a customer that is depositing unexplainably large amounts of cash into their account. These transactions began suddenly, have no clear economic purpose, and coincide with news stories about an arrest of the customer for the sale of drugs. This new cash activity would likely trigger an alert within a financial institution’s transaction monitoring system, which would then generate an investigation and possibly a SAR filing for referral to law enforcement. In connection with that investigation and/or repeated SAR filings, a financial institution may choose to close that customer’s account because they, understandably, do not want to do business with someone who may be committing crimes and laundering money. This is a risk-based customer exit decision.

In a different scenario, an institution may look at its customer base and assess that individuals receiving substantial international wires from high-risk jurisdictions into their accounts in the United States represent a more substantial risk profile than the institution would like to be responsible for. This appears to have been the case for Naafeh Dhillon, one of the customer’s whose ordeal was covered in the Times coverage. In these situations, institutions may be concerned about the regulatory scrutiny they’re receiving in relation to certain types of customers or are seeking to shift their business away from these customers due to global conditions. This broader exit decision is an example of de-risking.

The reasons behind de-risking vary and can be legitimate. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many financial institutions de-risked customers with relationships in Russia and Crimea, closing accounts to mitigate sanctions and financial crimes risks. They didn’t determine that these customers were actively committing crimes, but rather that their jurisdictional and sector-based proximity to risk was too great to maintain the relationships. Other common areas where de-risking has been seen is in relation to certain business types. Money service businesses (MSBs), pawn-shops, and cash-intensive businesses have a higher general risk for money laundering and often require enhanced monitoring to responsibly bank. Because of this, many institutions will either not bank these customers or may choose to exit these sectors entirely.

What the Times does is collapse these two distinct account closure scenarios into one, making the argument that risk-based exit decisions and SAR reporting are being managed improperly and are responsible for de-risking. This is simply not an accurate interpretation of what is happening. If they want to zero-in on the problems surrounding de-risking—and there are substantial ones—they should examine who is making the business decisions to exit markets, sectors, and customer segments and what is driving those decisions. And here’s a hint: it’s the cost of compliance.

What the Times is doing is improperly directing fire at investigators who are simply trying to follow the facts with regards to customer behavior and by extension, protect the financial system. In fact, within most institutions, risk-based customer exit decisions come as the result of a robust process, requiring multiple SAR filings and the deliberation of internal committees. The people deserving of public ire are those making these broad de-risking decisions without regard for the disruptive impact on individuals and businesses.

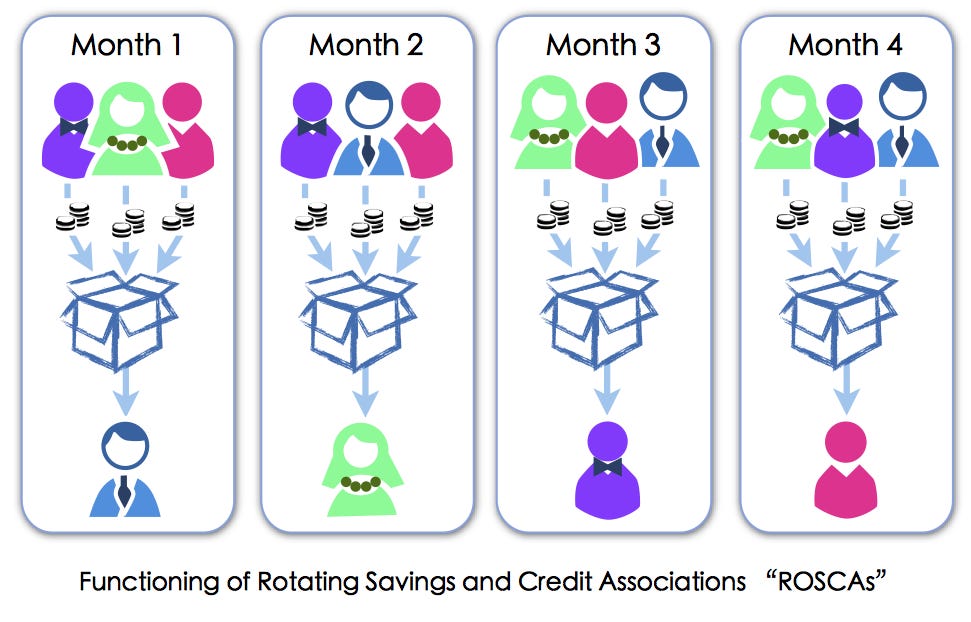

Furthermore, while this series focuses on how customers may inadvertently trigger regulatory scrutiny, they fail to report that violations of institutional terms of service are also a key driver of account closures. One of the examples presented in the Times November 5th article centers on Rosanna Bynoe, who utilized her JP Morgan Chase account to operate a Susu, a rotational savings vehicle common in immigrant and African American communities for collective savings and loan provision. In this case, the writers claim that the bank was concerned that the Susu was being utilized for fraud and that this led to Mrs. Bynoe’s account being closed. However, although the account may have been flagged for potential fraud risk, the more likely scenario is that operating a Susu or a Rotational Savings Group—in which a financial institution may be holding money for individuals other than the listed account holder—is likely a violation of that bank’s terms of service.

Many banks outlaw certain types of customer arrangements, particularly those that involve issues that constitute a legal gray area, such as involvement with cannabis sales and prostitution, or present potential vectors for fraud, like Susus. The distinction here is that rather than account closure decisions related to these terms of service violations coming as a result of a risk-based customer exit decision, they are coming as a result of the simple presence of certain account characteristics. This doesn’t mean that the decision to close these accounts is right, nor does it mean that these accounts were closed as a result of an investigative process that positively proved that they had committed financial crimes. It simply means that the account was identified as being used for something the institution would rather not be exposed to. Is this wrong? Maybe so—but banks have a right to make rules governing the conduct of their customers. There are certainly ways that regulators can disincentivize this behavior on the part of banks, but that’s not really discussed by the Times. I also think it’s important to note that there are now institutions that specialize in facilitating rotational savings organizations like susus and may be a better option for these consumers to make sure their accounts will remain open.

What troubles me most about this series of articles is that there’s an insinuation that SAR filings may create black marks on customer’s reputations for no reason at all when the bank secrecy system was designed with just the opposite goal in mind. The reason that the divulging of SAR filings is a crime is because it is understood that any such filing is an unverified accusation and that while beneficial to law enforcement, filings should not be public knowledge. This reporting by the New York Times seems to imply that SARs should be publicly known and that there should be some sort of court of law for adjudicating their filing. When the point is that they should only be used by a knowledgeable law enforcement professional to support the investigation of criminal activity.

I guess what frustrates me about this is that a lot of this information isn’t that hard to find and series like this create unnecessary fear, raise the specter of impropriety and focus anger on the wrong people. De-risking is bad and sudden account closures have a disruptive impact on people’s lives but the Times staff should have done enough research to know who to point the finger at.

BEST – Reuters Highlights the Reality of Remittance Activity Along the US-Mexico Border

In August—a few weeks after I published my interview with Rich Lebel—a powerful special report was published by Diego Ore of Reuters. The result of months of substantive interviews with individuals intimately involved with the process, Ore’s report pulled back the curtain on the expansive money laundering apparatus built by organized crime along our southern border to launder the proceeds of drug tracking and other crimes via money remitter businesses.

While it is widely known that the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartels have been using remitters to conduct money laundering for some time, this was a truth observed predominantly by law enforcement, financial institution insiders, and organized crime itself—until now. Ore took the unique approach of going beyond indictments and court testimony to interview the people being paid to conduct this money laundering. Real people living along the border and struggling with poverty, who have been enticed by the funds they can earn to support their families by following instructions and not asking questions.

Essentially, Ore’s reporting highlights an extensive community of individuals recruited by the cartels and paid to facilitate the movement of the cash proceeds from drug trafficking to Mexico from the United States for use by criminal organizations. For the individuals involved, their roles are rather detached and asynchronous. They’re given instructions about what they’re supposed to do—usually sending funds across the border via a remitter or taking funds sent to them by someone else and moving those funds to accounts controlled by the cartels—and are paid a fee for their work, but they don’t know much beyond that. They are a widespread network of mules, given instructions but not integrated into the fabric of the criminal networks they’re contributing to.

As Ore describes, this activity has been on the rise, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which made other methods of money laundering more difficult than they were previously. But what is really stunning is how closely linked this process is to the economic welfare of these border communities. Through his interviews with participants, Ore demonstrates how cartel activity has become a component of everyday life as well as the ease through which criminal organizations have used money remitters to thwart regulatory reporting structures on a systematic scale. The sentiment one comes away with is that it is extremely difficult to extricate the economic destiny of Mexico’s poor and working class from criminal organizations and that participation is not a limited phenomenon exclusive to those with questionable morals. A career as a part-time money launderer along the border is now mainstream.

And Ore’s coverage does not shy away from the impacts of this mainstreaming—he shares the real-life experiences of those who have tried to stop assisting the cartels and how this has often ended in the murder or kidnapping of their friends or family. It’s a piece that’s quite clear-minded about the reality of the moment, which is refreshing, but also leaves the reader frustrated about why this issue is not receiving more attention within both the United States, but more importantly, within Mexico.

And attention it got. Days after the piece was published, the President of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, aggressively refuted the reporting, stating, "Reuters, they are some deceivers, liars." Of course, the facts of the article don’t lie. Ore successfully weaves accounts from federal court cases, interviews with more than two dozen participants, as well as law enforcement experts to paint a damning portrait of the situation—the Mexican government just refuses to acknowledge the truth. Ore’s reporting is that unique piece that successfully depicts the human toll of financial crime while also putting it into a wider context, imploring us to act.

WORST – The Supreme Court’s Corruption Conundrum

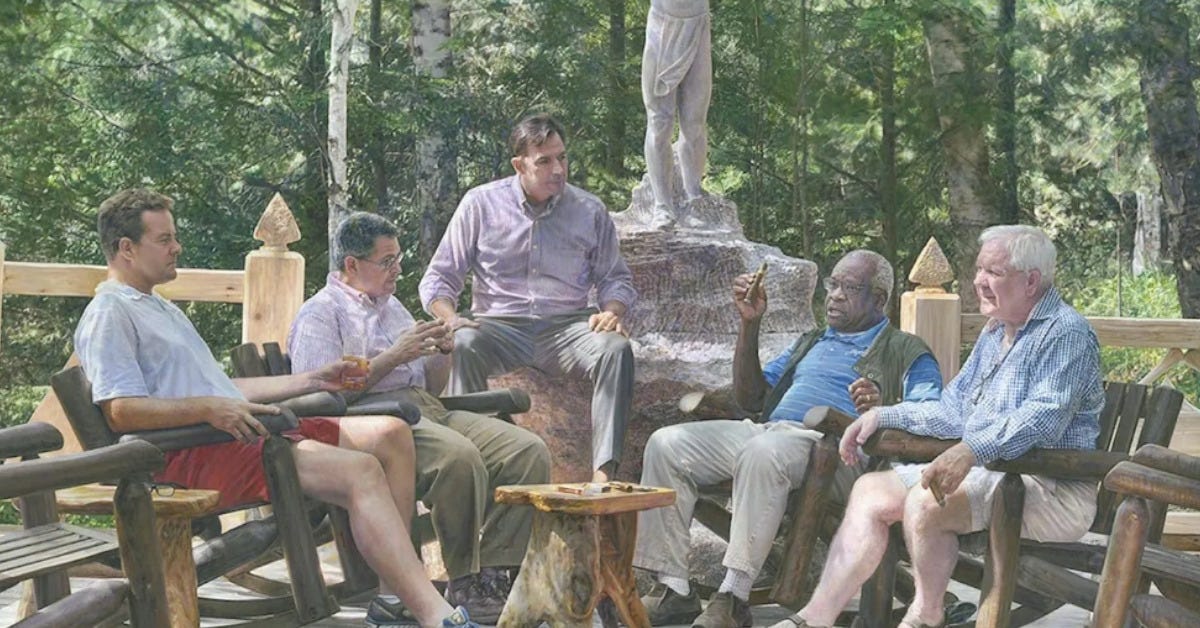

In recent years, I’ve often wondered if it’s even possible for us to hold public officials accountable for misconduct, especially the most powerful among them. Most notably, we’ve seen Donald Trump be subject to no less than 5 criminal investigations, but he is still the prohibitive front-runner for the 2024 Republican nomination for president. But this year’s most disturbing case has definitely been that of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Through the dedicated reporting of a number of media outlets, including Propublica and the New York Times, it was revealed that over the past 30 years, Thomas accepted millions in unreported gifts from wealthy benefactors with business in front of the high court, including vacations, homes, and tuition payments for relatives. These benefactors, including billionaire Harlan Crow, have denied that the gifts constituted any undue influence on Justice Thomas. But as commentators on both sides of the aisle have remarked—it’s awfully rich to argue that taking a man on 38 all-expenses paid vacations would have no influence on his judgement.

As Randall D. Eliason, former chief of the fraud and public corruption section at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, outlined in a May guest essay for the New York Times, there’s a darker truth to all of this, which is that at the same time Thomas has been accepting these lavish gifts he has been working to legitimize their legality through his rulings on the court. From the 1999 United States v. Sun-Diamond Growers of California, to Skilling v. United States, to McDonnell v. United States, to the most recent Percoco v. United States, federal laws prohibiting influence peddling activities such as the giving of gifts and the granting of special privileges have been significantly whittled down. Specifically, honest services wire fraud—which has historically been used as a tool by federal prosecutors to target corruption—has been systematically narrowed under accusations of “vagueness,” with the Supreme Court ruling that the law has only been violated if corrupt acts consist of quid-pro-quo arrangements in which a direct act is performed in exchange for a direct material benefit.

In order to constitute honest services fraud, the court contends that the conduct must be tied to an official act, or “…a decision or action on a ‘question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy’; that question or matter must involve a formal exercise of governmental power, and must also be something specific and focused that is ‘pending’ or ‘may by law be brought’ before a public official.” The function of this is that corrupt acts that cannot be tied to one specific decision, policy shift, or ruling, in almost explicit terms, cannot be deemed honest services fraud. So long-term patronage relationships, like that of Justice Thomas and his wealthy benefactors, are conveniently exempted from definitions of corruption. The precedent that corruption is fine, as long as it’s a little ambiguous is pretty disgusting and what’s even more troubling is that one of the main arbiters of that definition is himself committing these illicit acts.

First things first, we should impeach officials who violate the public trust and commit corrupt acts, including Supreme Court justices. Without those individuals removed from the bodies that make, implement, and interpret our laws, we have no hope of implementing a just legal framework to fight bribery and corruption. Furthermore, we should make Supreme Court justices term limited. The lifetime terms of each Supreme Court justice not only make their appointment and confirmation politically fraught, but also makes potential corruption extremely difficult to dispense with. If Clarence Thomas had a served a 10-year term, his corruption would still have had a substantial impact on American jurisprudence, but it would be significantly less that the nearly 30 years of tainted decisions that we’ve been forced to endure. And finally, we need to take a hard look at our corruption statutes, and work to create un-ambiguous language that further bars broad-based influence-peddling. Our definitions of illegal acts have to match the manner in which these actions manifest in the real world. Nobody—save maybe Forest Gump or Doctor Evil—would try to bribe a public official by telling them explicitly, in writing that they would give them $1,000,000 if they vote no on a bill, so why are we accepting that this as our legal reality? Corruption is corruption is corruption—let’s treat it that way.

BEST – The Quiet Revolution of the Corporate Transparency Act

Since the passing of the CTA, I’ve been closely tracking the journey of its implementation. Although quietly enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2021, the undertaking was anything but insignificant. To craft the legal standards for compelling all corporate entities within the United States to report their Ultimate Beneficial Owners to the US government and to create a national registry for beneficial ownership information in the space of just two years, which would allow law enforcement to use UBO information as a component of criminal investigations and for banks to use it as a means to assess the risks of customer relationships. Anyone who has worked in the government knows that this is a huge ask, with both public and private sector stakeholders clamoring for answers and a high risk for complications. Would the registry be ready on time? Would the legal standard for reporting be clearly articulated? Could criticism of its implementation cause public ire?

Well, I’ve been pleased to see that thus far, the US Department of Treasury has been able to weather the storm rather effectively. In compliance with the CTA, the federal government has issued rules establishing the information that is required to be collected from corporations within the United States, outlined the individuals who will have access to the beneficial ownership registry housing that information, and articulated a clear schedule for how the registry will be launched. In fact, just days ago, FinCEN began accepting Beneficial Ownership Information Reports (BOIRs) from corporate entities.

According to FinCEN’s schedule, as of January 1st, new corporate entities that are formed are required to submit their information to the registry. Existing corporations will have until January 1, 2025 to register themselves, and authorized government agencies and financial institutions that meet the requirements of the final rule will be issued access in stages throughout 2024. This swift implementation is a phenomenal achievement, especially given the widespread resistance to implementing a beneficial ownership registry that still persists today.

Critics of the legislation consist primarily of business leaders, who contend that the registration requirements would create burdens for the formation of businesses and interfere with the privacy of individuals—arguments that I personally think are weak and verge on dishonest. Fortunately, arguments outlining the overwhelmingly positive impact that the CTA would have on curtailing criminal behavior and eliminating the useability of shell corporations for illicit activity overcame these claims. The final bill was passed with a veto-proof majority, ensuring it became law even without President Donald Trump’s signature. It’s encouraging to see that the implementation is also moving forward undeterred.

Furthermore, it’s good to see that FinCEN has been exceptionally active in its responsiveness to stakeholder concerns during implementation. While there have been well-founded criticisms about the rules surrounding how BOIRs should be completed, what the manner of financial institution access should be, and how data from this new registry should be reconciled with customer-provide beneficial ownership information, FinCEN has responded quickly, demonstrating that it’s receptive to constructive input and special considerations. The Small Entity Compliance Guide and Interagency Statements throughout the rulemaking process show the adaptability and responsiveness that will be crucial for the registry to be successful in the long-term. Even if the outstanding issues are not satisfactorily settled in 2024, I would much rather we have substantive debates about how the registry is governed and operated than argue about whether it should exist at all. This is progress.

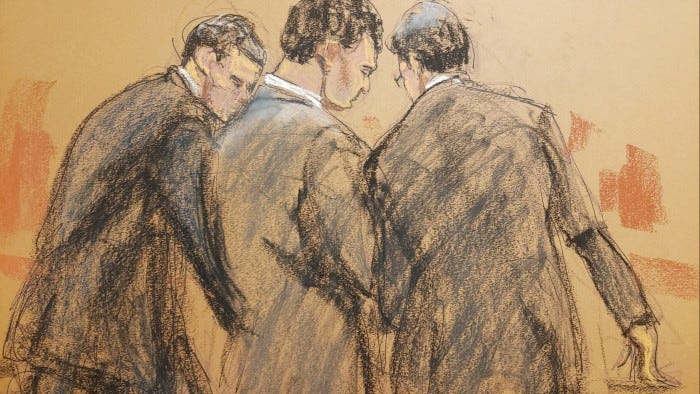

WORST – Bob Menendez Just…Being Bob Menendez

As if Clarence Thomas’ blatant corruption wasn’t enough, it seems like Senator Bob Menendez saw it and said “Hey, hold my beer.” In September, Menendez faced the first of three indictments, alleging that he used his influence to lobby on behalf of the Egyptian government and interfere with a prominent New Jersey real estate developer’s bank fraud trial. He later faced a superseding indictment alleging that he operated as a foreign agent on behalf of Egypt and then faced a second superseding indictment only days ago, alleging that he made positive statements about the government of Qatar to help the same New Jersey developer to secure investments from a company tied to the country. Needless to say, someone seems like they’ve been busy.

The Menendez case has been a lightning rod for media attention given that this is his second brush with corruption charges, the first being charges of bribery, conspiracy, and honest services fraud in 2015 for payments and gifts he received from a New Jersey eye doctor. That proceeding ended in a 2017 mistrial and Menendez lived to fight another day. There is also additional novelty here, given that federal authorities recovered $480,000 in cash and over $100,000 worth of gold bars during a search warrant of Menendez’ home in 2022.

The ridiculousness of the take here is that the senator continues to claim he is a victim of profiling because he is Latino and argues that he was keeping the funds in his home in the form of cash and gold bars “because of the history of my family facing confiscation in Cuba,” despite the fact that these are such obviously falsifiable lies. During the search warrant, the cash was recovered in envelopes covered in the fingerprints of the real estate developer he is alleged to have received the bribes from and in December, it was uncovered that the gold bars found in his home were tied to a police report filed by the same developer in 2013 claiming they were stolen. There’s such a direct line demonstrating the illicit payments it is almost comical.

And yet, Menendez has steadfastly refused to resign, even as Democrats have almost uniformly called for him to step aside. My hope is that the 2024 democratic primary for his seat will be a non-event, with Representative Andy Kim easily defeating him and Menendez’ lies fading to the background in advance of the general election. Honestly, judging by this photo of Andy Kim he seems like he’d be a significant improvement:

BEST – The US Reckons with China’s Criminal Footprint

Over the past decade there’s been a paradigm shift observed in global money laundering patterns. While there have always been flows of illicit funds and both individuals and organizations that facilitate the cleaning of dirty money throughout the world, a new actor has risen to take a central role in facilitating the operations of transnational criminal organizations: China.

While I’m not referring specifically to the nation-state—Chinese nationals and the companies, resources, and property they control—have become indispensable to the operations of criminal organizations and the laundering of their illicit proceeds. This development has grown out of a mutually-beneficial relationship in which Chinese currency restrictions and the needs of transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) operating in North America have synced up. The Chinese are looking for ways to evade currency restrictions to get their hands on dollars and move their money out of China, while the criminal organizations need a way to clean their drug proceeds and convert them into usable pesos. Meanwhile, the general consensus is that while Beijing is not explicitly directing this activity, it has done little to stop its growth.

For a long time, TCO money laundering and the conversion of pesos to dollars was facilitated by Black Market Peso Exchange, in which brokers, typically Columbian or Central American, negotiated the movement of funds between the US and Mexico by depositing funds at US banks, using those funds to purchase goods that were then shipped to and sold in Mexico—typically fraudulently—in order to yield pesos. Over time, both the financial crime controls in the US and in these countries have improved, making it more difficult and expensive to launder money this way. This shift created an opportunity for Chinese actors to enter the market, offering lower rates.

Utilizing international trade, Chinese banks, and the FinTech capabilities of apps such as WeChat, these Chinese actors offer almost instantaneous funds transfers for their clients, operating a sophisticated network of criminal funds flows.

At the same time, China has assumed a major role in the flow of Fentanyl and synthetic opioid analogs to drug trafficking organizations in Mexico, facilitating their production while the cartels handle distribution and sales throughout the United States. In a way, Chinese nationals act as the cartels’ bankers as well as their suppliers, making them indispensable to drug trafficking networks globally and implicating them in hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths.

While I was serving in law enforcement, I observed the growth of this relationship first-hand as more and more Chinese money launderers for hire were central to a variety of major cases and the focus within the opioid epidemic shifted from pill diversion to the widespread distribution of fentanyl. It also quickly became clear to me why this paradigm was so intractable. In the past, money laundering was occurring via networks across North and South America, in countries where the US had clearer pathways to influence government policy and officials were more willing to assist the United States in obtaining necessary financial intelligence. But China has been a financial intelligence black hole.

Requests for Mutual Legal Assistance asking China to assist US authorities in identifying Chinese money launderers would go unanswered and they would be uncooperative in identifying relevant documentation if it implicated their citizens. Moreover, it has taken the US law enforcement apparatus some time to recognize this the seriousness of this activity and shift focus to confront this threat.

It appears that finally, a critical mass of attention and government resources within the US has been marshalled to address the outsized role of Chinese nationals in the operation of TCOs and global money laundering. Although focus on China has been growing in law enforcement circles since 2020 and the AML Act dedicated resources to studying money laundering by Chinese nationals, 2023 saw a number of promising developments, with increased congressional attention on the issue and numerous prosecutions of Chinese actors for drug trafficking and financial crime offenses, but also diplomatic actions signaling that the threat of China is being taken seriously and that we are finally fighting back.

In March and April, two separate congressional sub-committees, the Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance and International Financial Institutions, and the Subcommittee on Healthcare and Financial Services, held hearings to discuss China’s impact on criminal financial flows entitled Follow the Money: The CCP’s Business Model Fueling the Fentanyl Crisis and China in Our Backyard: How Chinese Money Laundering Organizations Enrich the Cartels respectively. In those hearings, expert witnesses, including John Cassara, an author, former intelligence officer and US Treasury Special Agent, and Channing Mavrellis, an expert on illicit Chinese financial flows and then the Illicit Trade Director for Global Financial Integrity, testified about the outsized role China is playing in facilitating global money laundering and specifically laundering related to Fentanyl trafficking.

Cassara and Mavrellis highlighted an increased need to examine the informal financial system to disrupt funds flows, as not only trade-based money laundering, but also China’s underground banking system and fei-chien or so-called “flying money” are central to the low prices Chinese nationals can offer cartels. There was also significant focus on the role of Chinese pharmaceutical companies in supplying the chemical precursors of synthetic opioids to the cartels in Mexico and how US actions, both from a law enforcement and diplomatic perspective, could work to crack down on this activity. I hope that discussions like these will continue and lead to significant action in both the legislative and executive branches, shifting policymaking and appropriations to sufficiently address the new normal.

2023 also saw a number of major enforcement actions against Chinese nationals for their role in facilitating the production and sale of fentanyl in collaboration with Mexican drug cartels and for the operation of international money laundering networks. There were numerous prosecutions released by the Justice Department in June and October targeting Chinese companies and their principals for their conduct in fueling the opioid epidemic and US and Australian authorities cooperated in dismantling a massive money laundering organization that spanned across Asia.

But some of the most encouraging developments are on the diplomatic front. During the recent summit between President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping, the leaders reached an agreement that China would crack down on chemical companies shipping the raw materials for producing synthetic opioids to Latin America and would resume sharing information related to suspected drug traffickers in certain international forums. The fact that these issues were front and center in Biden and Xi’s bilateral discussions signals that US officials at the highest levels recognize their importance and the critical opportunity we have to use global cooperation to stem the flow of lethal drugs into the United States.

But of course, there’s significant room for improvement here. The most ideal development for progress would be for China and the United States to revisit their Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) to further codify the terms of cooperation between criminal investigators in the two countries. Increasing visibility into Chinese financial institutions and internal activities would have a major impact on the disruption of money laundering networks.

Of course, this issue is rather fraught. Aspects of the MLAT were suspended by China in 2020 in connection with pro-democracy protest actions occurring in Hong Kong. But this is of course a game of 3-dimensional chess and much has changed since then. China’s economy is suffering a significant downturn and capital flight is a major concern of the regime. Perhaps China’s fiscal instability presents the opportunity for a unique breakthrough?

Furthermore, law enforcement can and should devote more resources to these issues, continuing to shift focus from old paradigms to confront this new reality. But the truth is, we can’t necessarily prosecute our way out of this problem, the issues at play here are also diplomatic and economic and we will be nibbling around the edges until we can find the appropriate mechanisms to obtain the information and cooperation we need to be successful.

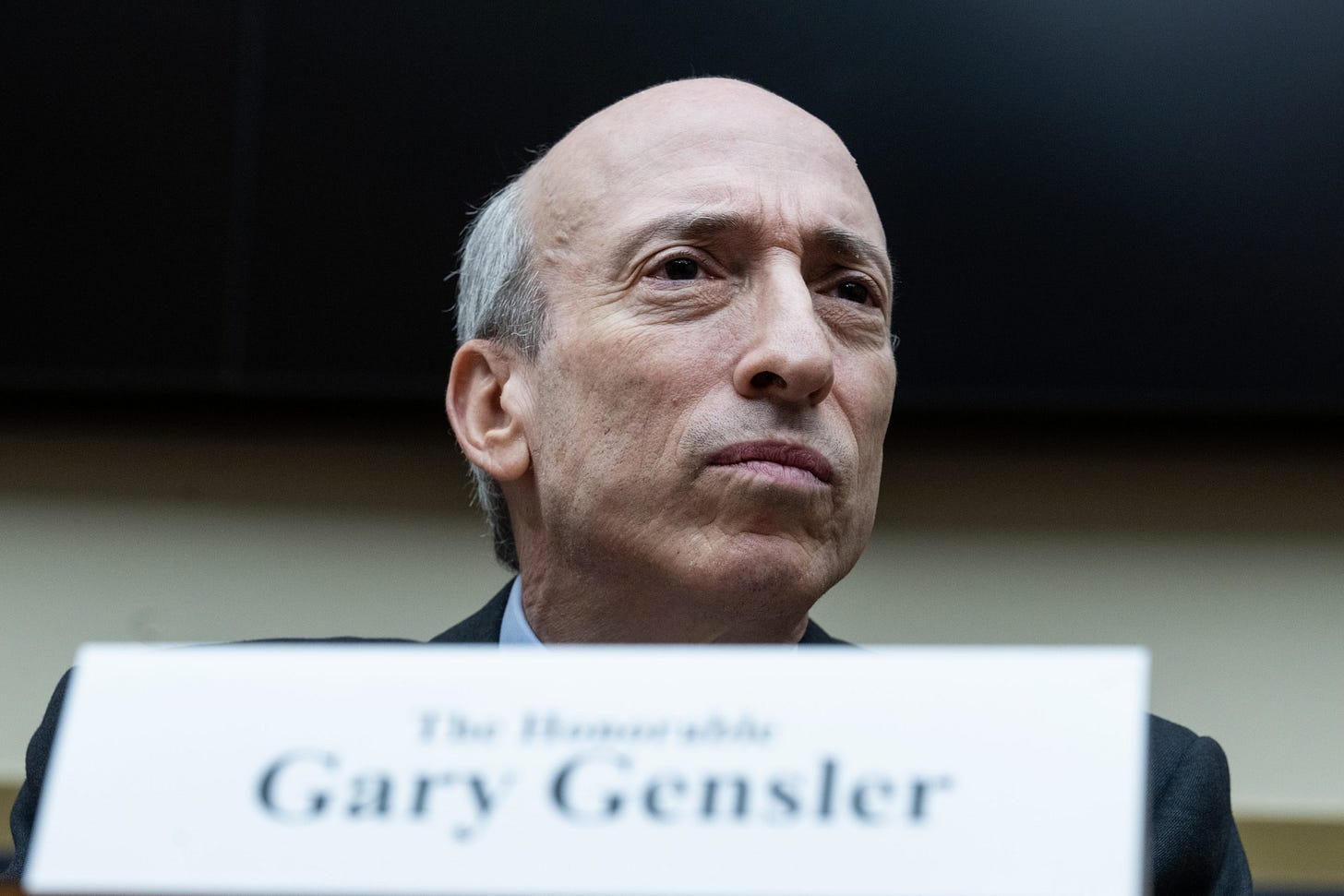

WORST – Gary Gensler’s Folly

It feels like SEC v. Ripple Labs has hung in the air for years. A case that held within it two crucial questions—are cryptocurrencies securities and if they are, what makes it so? The case was the first in what would become several suits by the commission against various crypto companies seeking to define the legal nature of crypto assets and protect investors. I often have forgotten about the Ripple case and then have come back to it upon realizing it still hadn’t been resolved. Like the spinach I bought weeks ago that I neglected to eat and then rediscovered in the back of the fridge—it doesn’t look so appetizing with age. But then in July, we suddenly had a summary judgement.

Judge Analisa Torres ruled that by definition, the retail sale of Ripple’s XRP token did not constitute a securities contract but rather a speculative purchase, while the institutional agreements that Ripple entered into could be deemed securities under legal precedent. And now I’m guessing you might be asleep? I don’t want bore you too much, but these details are important. The central crux of the case comes from a legal standard known as the Howey Test. A four-pronged test that was defined by the 1946 Supreme Court opinion SEC v. W. J. Howey Co. and indicates whether an asset or contract qualifies as a security. The test defines an “investment contract” as consisting of the following:

1. An investment of money.

2. The existence of a common enterprise, represented by a horizontal commonality or an understanding that the investor’s assets are pooled and that the fortunes of each investor is tied to the fortunes of other investors, as well as the success of the overall enterprise.

3. And with the reasonable expectation of profits due to the managerial efforts of others.

In the Ripple case, Judge Torres concluded that the institutional contracts that Ripple entered into with investors were just that, investment contracts. They had been sold on certain expectations of return via promotional materials, much like an investment prospectus. However, with Ripple’s progammatic sales—or retail sales by individual purchasers on cryptocurrency exchanges—she was unable to come to the same conclusion.

Torres contended that although the first two elements of the Howey Test were met by the retail sales, the third was not. While retail purchasers were investing money and taking part in a common enterprise—likely expecting profit—they didn’t purchase XRP with the expectation that these profits would come due to the managerial efforts of others. In fact, Torres highlights that the retail sales of XRP were distinct from its institutional sales in that they didn’t involve “promises or offers,” and once the token was launched, retail purchasers were often obtaining it in the secondary market without any direct contact or communication from Ripple Labs.

But what does this all mean? The impact of the ruling can’t be understated. Although it was a split decision, it struck down the SEC’s interpretation of XRP as a security and put in doubt a notion long held by Chairman Gary Gensler, that almost all cryptocurrency tokens (with the exception of Bitcoin) are securities and should be subject to SEC rules.

But more broadly, what the decision underscored was the problematic approach that has been taken to regulate cryptocurrencies over the past five years.

Although Gensler himself only began leading the Securities and Exchanges Commission in 2021, even before his tenure, the approach taken to regulating digital assets was consistently inconsistent. Although cryptocurrency exchanges have been regulated as Money Services Businesses (MSBs) under the jurisdiction of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and are subject to FinCEN Suspicious Activity Reporting requirements, there has been significant confusion about the regulatory issues surrounding the assets themselves, chiefly, are they securities, are they commodities, or are they a secret third thing?

This has not been helped by the fact that both the SEC and the CFTC (Commodities Futures Trading Commission) have staked (haha get it) conflicting claims about the jurisdictional scrutiny of the space, even down to the definition of specific currencies. In 2018, the CFTC argued and a US district court judge agreed that "Virtual currencies are 'goods' exchanged in a market for a uniform quality and value. ... They fall well within the common definition of 'commodity'.” But then in 2022, Gensler argued that proof-of-stake currencies likely constitute investment contracts and were therefore securities. In early 2023 he expanded his contention remarking that, “Everything but Bitcoin,” may be subject to SEC jurisdiction. And along the way each side has changed their opinion ever so slightly in subsequent public appearances. At the same time, the SEC and CFTC have issued enforcement actions against a number of crypto companies, arguing each of their respective positions and creating an even greater cloud of uncertainty surrounding these jurisdictional questions.

This approach—what I would call regulation through enforcement and innuendo—has created the situation we face today, a sector in desperate need of regulatory guidance but with watchdogs who refuse to publish anything concrete. And the Ripple Labs outcome is simply another confusing piece of this puzzle. Of course, the industry has taken this as a victory for their cause and believe it portends favorable decisions in other crypto cases. But I really think that the best thing for the industry would be to make the legal framework here abundantly clear.

There’s a number of ways to accomplish this. Some have called for crypto legislation that would more explicitly define the legal framework for digital assets in order to bring the confusion between the SEC and the CFTC to an end. The Lummis-Gillibrand legislation is one such bill that would define most cryptocurrencies as commodities but with special scrutiny for where there may be SEC implications. Others have called for a new regulatory agency for digital assets all together. What I think would be an easier lift is if the SEC issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking outlining its current position. Perhaps they attempt to further define the Howey Test in response to the Ripple Labs ruling and/or provide greater clarity to institutions going forward about when coins constitute investment contracts. The SEC is constantly making rules regarding other matters, why is it so reluctant to provide clarity here?

And this is coming from someone who really recognizes the need for regulation. I’m not naive, there are many people doing irresponsible things in this nascent industry that should be penalized for it. But what has been created from the lack of communication by the regulators is an ecosystem of distrust and frustration. Tell people what the rules are and they can play by them, if the courts challenge your rules, then you change them, if people break your rules, then you can punish them. But cryptocurrency ain’t your father’s stocks. Stop trying to act like you don’t need to make any new rules.

BEST – Google Cloud’s AI Gamble

I’d like to close with some hope for the future (I know, a bold move in a year when two octogenarians are set to have a rematch for the White House) but I think we need some promise that things can and will improve, and honestly I think some innovation is just what the doctor ordered. In June, Google Cloud launched AML AI, a risk monitoring solution powered by artificial intelligence that uses machine learning and existing financial institution data to better identify risks and suspicious activity for reporting.

In a significant break from industry orthodoxy, AML AI seeks to replace traditional rules-based transaction monitoring with a constantly evolving, risk-based analysis of customer data. The intelligent algorithm continuously analyzes customer profiles and behavior in context with the risk tolerance of the institution to generate a risk score that then prompts investigators to pursue further inquiry. Early outcomes following implementation of the solution at HSBC and Banco Bradesco have been compelling, with a 60% reduction in false positive alerts and a 200-400% increase in confirmed suspicious activity that has been detected and reported.

I’ve got to say I was and still am skeptical. Although AML AI has generated favorable outcomes in its initial use-cases I can see a few problems here. One being that many institutions do not just have a problem with their transaction monitoring methodology, they also have fundamental issues with the integrity of their Know Your Customer data as well. For those that aren’t familiar—this is the underlying customer data collected by the institution at onboarding. Investigators often rely on KYC data to effectively analyze whether unusual activity detected during transaction monitoring is in line with the profile of the customer to determine if it may constitute suspicious activity and requiring the filing of a SAR.

If these AI models are basing their analysis on customer KYC data that hasn’t been properly collected and validated, the AI’s ability to effectively assess risk may be compromised. AI is only as good as the data you can provide it, and I’m not sure if the data at every financial institution is robust enough to power an accurate algorithmic analysis. Furthermore, I wonder what the implications of this model would be for regulatory examination. Analysis of an institution’s transaction monitoring program via the review of their rules and methodology is an important component of assessing whether the institution is taking a robust, risk-based approach to monitoring its customers. While we can compare outcomes before and after the AI implementation to see that there are less false positives and more positive identifications of illicit activity, how do we continually assess the health of these algorithms and diagnose when there are issues? Can improper data cause the algorithm to veer off-track? How can we tell and how can we make sure it gets back to generating satisfactory outcomes? Just a bit of healthy skepticism.

Even so, I’m excited by the possibility AI brings to depart from the arbitrary nature of rulemaking within our transaction monitoring systems, moving away from reporting thresholds as hard limits, and finding a way to craft an intelligent approach that can more deftly recognize attempts at obfuscation. I’m sure AML AI will improve and other, competing solutions will come along, maybe some that propose solutions to the questions I have. Until then I’m cautiously optimistic, observing their development from afar and curious about how they will impact institutions and investigators in the future. Who knows, at some point maybe AI will be able to decide when activity is suspicious and automatically write the SAR, with BSA Officers simply saying yes or no to its filing. A scintillating yet chilling thought!

![The Lord of the Rings - Frodo says: “All right then, keep your secrets” [meme template] : r/MemeRestoration The Lord of the Rings - Frodo says: “All right then, keep your secrets” [meme template] : r/MemeRestoration](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!d7Di!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F351b26fd-650f-48cd-879d-7993b4692ce7_1000x734.png)